In our opening series, let’s call it season 1(Female Health) of our newsletters, just to make it interesting. I’d like for us to talk or rather look at issues that affect mostly women in rural societies. The aim is to stimulate you to think and consider what you might be able to do in your capacity to help bring awareness to others in relations to these matters and perhaps you could help in the fight to combat these issues.

Most people who live in urban or model societies are not too familiar with such issues, but these issues tend to filter into the urban society, because women in urban areas might be victim, they could be mother of children that are affected or might be affect, or as a man you might find yourself married to a woman who underwent such experiences/ordeals.

In Season 1 episode 1 Let’s look at:

Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C)

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) comprises. ". all procedures involving partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons."

It is estimated that at least 200 million girls and women have undergone some form of genital mutilation/cutting, and if the practice continues at recent levels, 68 million girls will be cut between 2015 and 2030 in the 31 countries where FGM is routinely practiced.

In 2008, the WHO/UNICEF/UNFPA Joint Statement classified female genital mutilation into four types: Type 1, 2, 3 and 4.

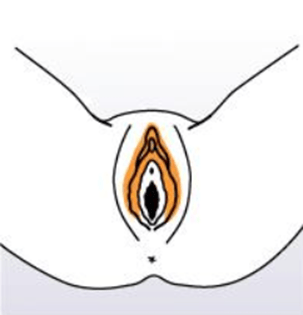

Type I

This is the partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the prepuce. Medically referred to as clitoridectomy. It is the most commonly practiced.

Type I

Type II

This type refers to the partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without surgical removal or cutting of the labia majora. It is seen mostly in countries like Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, and Mali. Though other countries practice it as well in smaller scales.

Type II

Type III

This refers to the narrowing of the vaginal orifice, with creation of a covering seal, by cutting and sewing the labia minora and/or the labia majora together—with or without excision of the clitoris. The procedure is referred to as infibulation. This is common mainly in north-eastern Africa, particularly in Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan

Type V

Refers to all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes (e.g., pricking, elongating, piercing, incising, scraping, and cauterization). The reasons, context, consequences, and risks of the various practices subsumed under Type IV vary enormously. These practices are generally less well known and studied than Types I, II, and III.

The affected age group is 0 -14 years, with the majority of girls being cut at the age of 5 years. Recent statistics reveals that a lot of victims with complications at present are between the ages of 15 to 49 years.

What are the reasons or motivations behind these practices, you might ask yourself. With the knowledge and freedom, you are privy to, you might even thing this is crazy, but this is a reality for most people and its not only in Africa. This is seen in the middle east, in Asia, Europe and majority in Africa.

The justifications offered for the practice of FGM/C are numerous and, in their specific contexts, compelling. The motivation for the practice is often linked to the perception of specific benefits. FGM/C assigns status and value both to the girl or woman herself and to her family.

Some common reasons given for FGM/C include that it ensures the following:

· A girl's or woman's status

· Marriageability

· Chastity, morality, and fidelity

· Preservation of virginity

· Health and fertility

· Beauty

· Hygiene/cleanliness

· Family honour/social acceptance

· Religiosity

· Male sexual pleasure

· Religious necessity/approval

According to Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data, the majority of women cite gaining social acceptance and inherent skill to please the male sexual partner as a benefit of FGM/C.

The majority of girls at risk of undergoing FGM/C live in Africa and the Middle East. In Africa, these countries form a broad band from Senegal in the west to Somalia in the east. In some of the countries such as Somalia and Guinea, 98% of women and girls, aged 15-49, have undergone some form of FGM..

The best available data on FGM/C prevalence, as well as information on health consequences attributable to FGM/C, comes from large-scale population-based surveys. We know these things happen as well in our region(SADC, especially type I and IV, However, the ability to make inferences from self-reported data is limited due to the following factors:

· Recall: It may be impossible for some women to remember any details regarding the experience, especially for those who had undergone the procedure in early childhood or infancy.

· Fear: Women and girls may fear reporting that they (or their daughters) have undergone FGM/C, due to legal sensitivities.

Despite these reasons, a number of hospital-based and epidemiological studies have been developed to provide a clearer picture of the national and global picture of FGM prevalence.

So why am I bothering to even discuss these things, what are the implications?

1. The immediate health consequences of FGM/C for a girl or woman depend on a number of factors:

· The extent and type of the mutilation/cutting.

· The cleanliness of the tools used and the setting.

· The physical condition of the girl or woman

In most countries, FGM/C is performed in poor sanitary conditions, mainly by traditional practitioners who may use scissors, razor blades, or knives. The lack of hygiene leads to severe infections and septicaemia (blood poisoning); additionally, the pain and trauma can cause severe shock.

Other immediate complications are tetanus or sepsis, urine retention, ulceration of the genital region, and injury to adjacent tissues. Hemorrhage and severe bleeding can result in death.

2. In the longer term, many women experience sexual, psychological, and obstetric problems. A number of serious health outcomes have been identified in medical reports:

· Gynaecological problems

· Psychosexual difficulties

· Obstetric complications

· Infertility

If women and girls do not receive appropriate health care as well as psychological and emotional care, these health impacts are further complicated. Many women might not be aware that the health problems they experience later in life are related to FGM/C; therefore, these problems go unreported.

The WHO Study Group conducted the first large-scale, international study to break through the silence and confusion around FGM/C. Based on the direct observation of more than 28,000 women in six African countries, the prospective study shows clearly that FGM/C (Types I, II, and III) is associated with an increased risk of obstetric complications, including caesarean section, postpartum hemorrhage, episiotomy, extended hospital stays, the need for infant resuscitation, and in-patient death. The risk and severity of complication varies according to the type of FGM/C, with Types II and III leading to worse outcomes.

In 2021, another research study provides qualitative evidence of the psycho-social impact of FGM and provides a framework for understanding ways FGM affects the sense of identity, self-esteem, participation in society and the overall well-being of the lives of women who have experienced it.

In simple English, women with Type I and II FGM/C have a significantly higher prevalence of long-term health problems (such as dysmenorrhea and vulvar or vaginal pain), problems related to abnormal healing, and sexual dysfunction.

They are also much more likely to suffer complications during delivery (perineal tear, obstructed labor, stillbirth) and complications associated with anomalous healing after FGM/C. Similarly, new-borns were found to be more likely to suffer complications such as fetal distress and caput of the fetal head.

The situation of mutilation gets so severe in some places that in countries such as Egypt, Kenya, Guinea, Somalia, and Sudan, the medicalization of FGM/C has constituted one of the greatest threats to abandonment.

Although FGM/C is usually performed by traditional practitioners, incidences of FGM/C medicalization have been increasing for some time. According to UNICEF, 1 in 4 survivors of female genital mutilation were cut by a health provider as of 2020. In Egypt, for example, mothers report that three out of four cases of FGM/C procedures performed on their daughters were provided by a trained medical professional. That is about 1.5 million girls and women have been cut by health care providers and 1.2 million of which were cut by doctors.

While medicalization most often refers to the shift from traditional practitioners to health care providers, it sometimes also refers to the use of medical instruments, antibiotics, and/or anesthetics.

“Doctor-sanctioned mutilation is still mutilation. Trained health-care professionals who perform FGM violate girls’ fundamental rights, physical integrity and health,” In collaboration with ministries of health and other relevant stakeholders, the UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme has employed a number of strategies to address the medicalization of FGM/C such as:

Prohibiting medicalization through decrees and development of adequate health policies

Training of doctors, midwives, and nurses on integrating prevention and counselling around the abandonment of FGM/C into services

Integrating FGM/C prevention activities into school curriculums

Conducting evidence-based advocacy work

From 2008 to 2013, close to 5,600 health facilities in 15 African countries integrated FGM/C into their antenatal and postnatal care routines. Over 100,000 doctors, midwives, and nurses were trained on integrating FGM/C prevention into services. This has contributed to the strengthening of capacities for FGM/C-related prevention, response, and tracking in the health sector.

In conclusion

Studies have described a lack of provider awareness of the prevalence, diagnosis, and management of FGM/C. Appropriately trained medical personnel could lead to improved communication, diagnosis, and documentation, and therefore to better health care and FGM/C prevention for future generations. It is important that training also include cultural, psychosexual, and legal information, along with medical and surgical care and obstetric management.

Good news as well is that In Sudan, a country with a high prevalence of FGM/C, the government in 2020, outlawed the practice of FGM/C and put in place a new law that criminalizes FGM/C. Anyone who performs FGM/C faces three years in prison and a fine.

Countries like Kenya and Nigeria also followed suit. As a side note, these practices continue to happen in our communities, but they are so minor that, they don’t attract attention from the WHO or the government. It is up to us now to speak out when we witness or experience such practices.

Appropriately trained medical personnel could lead to improved communication, diagnosis, and documentation, and therefore to better health care and FGM/C prevention for future generations. It is important that training also include cultural, psychosexual, and legal information, along with medical and surgical care and obstetric management.

Raising community awareness of the harmful effects of FGM/C is critical to addressing the demand for it. With the potential to reach a global audience, the media can play an important role in efforts to end FGM/C. Awareness can be raised through traditional media such as newsprint, television programming, or radio, or through more recent innovations such as social media platforms.

Women’s attitudes toward the practice have also changed drastically, as support for FGM/C fell from 82% in 1995 to 54% in 2020. The numbers are slowly declining world wide.

References